Retro Rick Bayless: Hot Sauce Time Machine

Tomatoes, chiles, garlic and onions–these four basic ingredients have been the flavor foundation of Mexico’s cuisine–and its signature salsas–for centuries. Used along with a few basic cooking techniques like fire-roasting, boiling, toasting and grinding, the combinations are impressive. Factor dozens of varieties of fresh and dried chiles in to the mix and you have a limitless array of stunning salsas with mindboggling possibilities.

The salsa-loving crowd in this country has caught on and manufacturers have responded. Gone forever are the days when our choice was limited to a hot, medium or mild tomato-based salsa. Today, customers can choose salsa by its flavor not just its heat level. Think roasted garlic, fresh cilantro, tomatillo, green pepper, black bean, etc. We are learning our chiles, too, from the ubiquitous jalapeño, to the floral-tasting yet hot habanero to the new darling of those in the know–smoky chipotle (actually a smoked and dried jalapeno). Salsa aficionados here are getting the message–chiles have flavor–not just heat.

The salsa-loving crowd in this country has caught on and manufacturers have responded. Gone forever are the days when our choice was limited to a hot, medium or mild tomato-based salsa. Today, customers can choose salsa by its flavor not just its heat level. Think roasted garlic, fresh cilantro, tomatillo, green pepper, black bean, etc. We are learning our chiles, too, from the ubiquitous jalapeño, to the floral-tasting yet hot habanero to the new darling of those in the know–smoky chipotle (actually a smoked and dried jalapeno). Salsa aficionados here are getting the message–chiles have flavor–not just heat.

Fortunately, salsa with flavor is not just some trumped up idea to spur sales. From one end of Mexico to the other, salsa is set out on tables to add not only zip but character to all sorts of foods–from simple eggs to roasted meats and vegetables. Sort of like how we use salt and pepper in this country. Each region, and indeed each cook, has their own specialties from the arbol chile-tomatillo salsa of Guadalajara to the thick, black, chile pasilla salsa spiked with pulque in Central Mexico.

In Mexico, there are essentially three kinds of salsa. First, there is the chopped ripe tomato, fresh chile and fresh cilantro “relish” that many of us know as “pico de gallo.” In Mexico, it’s made fresh for every meal; its closest cousin here, may be the “fresh” salsas sold in refrigerated cases.

Mexico’s thin, vinegary, very spicy chile sauces keep better and consequently are more readily available. In this country, we think of them as ‘hot sauces” and they are somewhat related to our Louisiana-style hot sauces (though in Mexico they have more body and flavor).

The best-known salsa style (and the kind that most easily translates to store shelves) is the classic Mexican salsas that are typically made with cooked tomatoes or tomatillos and fresh or dried chiles. Whether the tomatoes or tomatillos (and onions and garlic, too) are boiled or roasted over an open flame depends on the penchant of the cook. Likewise the selection and treatment of the chile.

The best-known salsa style (and the kind that most easily translates to store shelves) is the classic Mexican salsas that are typically made with cooked tomatoes or tomatillos and fresh or dried chiles. Whether the tomatoes or tomatillos (and onions and garlic, too) are boiled or roasted over an open flame depends on the penchant of the cook. Likewise the selection and treatment of the chile.

Salsas have gained in popularity in recent years not only because they offer a wide range of flavors but also because they do it (usually) with no fat, lots of vegetables and a minimum of sodium.

By now just about everyone knows that salsa outsells ketchup in this country. What some folks may not realize is that we are beginning to use salsa much like we use ketchup–as an ingredient in recipes. Just think about the recipe contestant who won a million dollars for her recipe featuring salsa, chicken and couscous. Surely that’s a sign to many on this side of the border–salsa can be so much more than a dunk for tortilla chips.

Salsas go with just about everything–from those crisp tortilla chips to simply prepared meats and poultry, to a myriad of appetizers. Let’s take a cue from Mexico where various salsas form the foundation of hundreds of classic dishes–from simple stews to complex preparations.

So get in the salsa groove and think beyond chips!

JeanMarie Brownson, Culinary Director

MORE THAN PURE FIRE: These are bottles of full-flavored passionate zing, delicious drizzled onto grilled meat or fish or eggs, stirred into bean soup, even shaken over French fries. Yes, it’s a condiment, but one that encourages generosity and a free spirit.

Rick’s Secrets to Good Food and Healthy Living

Over the last several years, I’ve become accustomed to an almost identical interrogation from practically everyone I’m introduced to. “How come,” they all wonder out loud, blurt out loud, “you’re so lean, if you’re a chef?”

It doesn’t really take much reasoning to parse the thought process: A chef gains notoriety by making really delicious food. Delicious food is rich food—the stuff that makes us fat. And the more delicious the food, of course, the more we indulge. If you’re a good chef, you… well, you should be at least pudgy.

Whether they’d admit it or not, I’d bet most of my interrogators want to ask is, What kind of freak is this guy? He spends all day in a great restaurant, surrounded by really good food, developing and tasting new dishes. Does he have some kind of eating disorder? Is he one of those weirdoes who’s into self-denial. Doesn’t he ever just sit down and dig in to the fruits of his own cooking?

Eating disorder? Everyone who knows me will attest that there’s no eating disorder, certainly no practice of self-denial. I love to eat—from morning to night. I do it for a living. I do it for a hobby. I do it with friends and family, and when I’m alone. I’m always thinking about, and talking about, my next (or last) meal. Without trying to sound grandiose about the whole thing, I’m a chef because food and the people I share it with enrich my life with endless diversity and unexpected pleasures. From my youngest years, food has been my bridge by to a full experience of life.

So, what’s the deal with my leanness? Abnormal metabolism or unique genetic make-up? I don’t think so, because I haven’t always been lean. In fact, I was a Hostess Cupcake, Gilligan’s Island reruns, chubby adolescent—totally unathletic. Some of that adolescent chubbiness fell off naturally during my last high school years, then slowly I started coming back—bit by almost unnoticeable bit. It’s a common story: By my mid forties, I’d accumulated at least 25 extra pounds—plenty noticeable on my average, 5-foot 10-inch frame.

That’s when I rather accidentally found myself on a path that led to my uncovering some useful basics about food (especially the role of delicious food, richness and indulgence) and about my body (what it needs—and when—to stay healthy). After several years on the path, when I stopped to reflect on my experience, I easily distilled six essential learnings. They’re personal learnings, to be sure, just right for me, but they’re learnings that helped me regain the balance we all seem to be striving for.

* * * * * * *

At my heaviest, several new ideas began percolating in my brain simultaneously. A friend started teaching yoga, and I found myself intrigued with her—yoga’s—approach to the body and its inseparable connection to the spirit. I knew of yoga’s purported stress-relief benefits and thought all that stretching could be a nice antidote to my fast-paced, late-night restaurant life. So I signed up to dabble in yoga first hand, expecting little more than temporary detox. I’d never been able to stick with—let alone excel at—any physical activity.

Okay, I loved the relaxation I felt after beginners’ yoga class—who wouldn’t?. But about four months into it, just when I was expecting to flag, I hit a yoga groove that led to some unexpected changes in the way I thought about myself. It was like my yoga practice was setting free some vision of my potential self. Longer, stronger, leaner, more lithe.

I liked it. In fact, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. Problem was, my reflection in the mirror didn’t match up with this inspiring new mental image. I looked lumbering and acted squatty. But knowing I’d uncovered something important about self-perception and yoga’s potential as a tool for change, I was fired up to push myself pass the yoga “dabble” to the real thing.

Essential Learning #1: My weight reflects a mental picture I have of myself. For me, yoga challenged my body in directions I’d never considered—unlocking a welcome new image of myself, unlocking physical (even spiritual) potential I’d never considered.

I made yoga progress little by little, tackling more and more vigorous approaches and demanding poses, though I certainly can’t say my body was transforming itself as quickly as I’d imagined. The squatty heaviness snickered at my — by then desperate — attempts to slide my hands under my feet or sustain myself for more than a few seconds in a lunge position. Not only did I feel stiff and weak, but I was trying to move around a fair amount of weight.

Which led me, in an uncharacteristically weak moment, to fleetingly, generically consider the question, Is it possible for a person to sensibly get rid of extra weight—without going on a diet?

Diets are something I’ve loudly railed against, having seen too much hype, too many unrealistic expectations, too many failures. I oppose them on (at least) two grounds—one nutritional, the other social. Most diets, after all, restrict what the dieter eats in quantity or variety, or both. Unrealistic quantity restriction frequently provokes the fear-of-starvation backlash (aka gorging), and narrowed variety not only becomes unsustainably boring, but it can be nutritionally unbalanced, even dangerous—unless you’re treating a serious medical condition, which I’m not. Our species developed as omnivores, after all.

And from a social perspective, diets can be isolating. I’d venture a guess that we’ve all known people who’ve used their diets as an excuse for not eating with the family, not going out with friends, and, in extreme but sadly frequent cases, not partaking in holiday feasts. Food may be the fuel for the body, but it’s also glue for the family, for the community.

I refused to go on a diet, but I decided I could take a closer look at what I was eating.

Like everyone, I’ve read a lot about the “empty calories” and growing portions in the American diet. I figured there must be some excess to cut out of my own diet—stuff I consumed without thinking, stuff I wouldn’t really miss.

Since I’m not a “yes, I’ll super-size it,” “sure, I’ll take fries with it,” fast-food guy, I didn’t have an easy target to start with. Until I landed on beverages. I was used to drinking sodas, sweetened “juice” drinks, mochas, coffee with cream, and I knew they were filled with a good amount of calories, “empty calories” most would say.

So I devised this plan: On an everyday basis, I’d stick with water (sparkling or still), coffee (black) and tea (no sugar)—plus a glass of wine or a beer with dinner.

To tell the truth, I hadn’t realized everything I’d been missing. I turned my chef’s training toward my beverage project and started doing tastings. I’d brushed past all the distinctive tastes of mineral waters, for instance. Different coffee varieties not only offered a multiplicity of flavors, but different brewing methods from drip to press pot to espresso showed a different side of each coffee bean. And tea—I’m almost ashamed at how little I really knew about the wide world of black, semi-fermented and green teas, not to mention all the herbal flavors that were easily at my fingertips.

For all of my adult life, I’ve been a flavor junkie. Well, a flavor and texture and aroma junkie. Like most chefs, I get off on the smoky pungency of chipotle chiles or the crunch of jellyfish or the head-spinning fragrance of white truffles, but I discovered that beverages as simple as water, coffee and tea can provide endless thrills, too.

That was the same time I started evolving toward another change—this time not in what I was consuming, just how much. I started cutting off a little part of my then normal-size portions—and pushing it toward the side of the plate. Ten percent to start with, then fifteen or twenty, maybe twenty-five. My goal certainly wasn’t to starve myself, just to see just what my body needed to feel full. I had to eat my food slowly—as slowly as you can in the fast pace of a restaurant environment—so that I wouldn’t gobble mindlessly, quickly through the whole portion without questioning my real hunger. And I realized I was practicing what I’d learned in yoga: listening to my body.

Over a few months, I’d weaned myself off about a quarter of what I’d been eating before, I’d lost 10 pounds or so, and I’d never felt hungry. Just good—and always ready for my next meal.

Essential Learning #2: No matter what weight-loss diet plans promise, monitoring the quantity of food is essential to maintaining healthy weight. I bristle to say it because it sounds so clinical, so un-delicious, but the real truth is: I need to monitor the quantity of calories I consume—calories, because different foods have very different concentrations of calories (more below).

I’ve always eaten some of everything—fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, meats, fish, eggs, dairy, all kinds of fat—even though I’ve been keenly aware that all the diet gurus, if you got them together, would raise their voices into a cacophonous chorus that would collectively denounce practically everything edible. All their contradictory barking left me wondering if any of them could be trusted to elucidate nature’s truths.

On the other hand, since I was in the process of scrutinizing what I eat, should I consider make some choice changes? Should I turn away from my beloved fresh-baked corn tortillas because Dr. Atkins has convinced us (at least for the moment) that carbohydrates are “bad” for us? Should a plate of luscious pork carnitas, simmered until crispy in its own fat, be banished because of Dr. Ornish’s fat-damning clinical studies? And should I avoid sugar and salt and coffee and commercially-grown vegetables with their pesticide residues and…I began to feel overwhelmed.

So I chose what some might consider the gastronomic equivalent of a nose-thumb, and I decided to eat a sensible amount of everything you find around the perimeter of the grocery store—the fresh ingredients that cultures have eaten for millennia, the unprocessed stuff.

Those are the foods that a chef most likes to work with anyway, the ingredients we find so inspirational. They’re piled high in traditional markets around the world. And “perimeter foods” have one very positive thing in common: Practically all nutritional researchers recommend them. Most agree that a varied diet balancing fresh fruits, vegetables, meats, fish, poultry, dairy, grains and legumes is the healthiest diet for most people. Good nutrition is that simple, that easy to understand, that sensible.

As a chef, I use the variety I find on the grocery store’s perimeter as my culinary challenge, too. How can I simply prepare rutabaga, for instance, that will make it thrillingly delicious? Or chicken livers? Or skate wing? Sure, we all gravitate to certain favorite flavors and preparations, but I’m convinced that being dedicated to eating a wide variety side steps the potential ping pong pull of nutritional debates and new discoveries.

(I dream of the day I’ll be able to go into McDonald’s and have the interaction go something like this:

Me: I’ll take a quarter-pounder.

Them: Lamb, venison or beef?

Me: I think lamb, and some fries—what kind do you have?

Them: Taro, beet and potato.

Me: Taro sounds good—never had taro fries. What sizes do you offer?

Them: Sorry, only our normal small size—we’re an everyday place. A sparkling juice to drink?

Me: Lamb, taro fries—no I think I’ll have a glass of Zinfandel.)

Essential Learning #3: Eating a wide variety of fresh ingredients is fundamental to nutritional fitness.

All this thinking about the fuel I was getting from different foods and beverages had led me face to face with questions about foods I wasn’t in control of. Meaning food I (or nature) didn’t really make. Processed foods, prepared foods, fast foods. All of a sudden, I had an interest in knowing what exactly was in that granola bar I was in the habit of buying, that bottle of barbecue sauce, that Styrofoam carton of ramen noodles I kept on the shelf in case of emergency. It didn’t take long to figure out that granola bar snack was way more packed with calories (200, for one variety I’ve bought, a number I’ve now taught myself to look at) than an average apple (about 80 calories), say. Though the outcome should have been the opposite, the granola bar frequently left me wanting more. It wasn’t as satisfying, especially when the apple in question was from the farmer’s market and filled with that distinctive perfume that only a locally grown, tree-ripened apple can have. Though I’ve never been a huge consumer of prepared, packaged or fast foods, I decided to make a bold step.

Essential Learning #4: Processed foods, many of the already-prepared foods and most fast foods have no place in everyday eating. As a believer in the resilience of the human body, I can’t deride a Big Mac every once in a while (I’ll even admit that I do like that special sauce). I simply decided that it has no place in my everyday breakfasts, lunches or dinners.

That’s when my life’s work—my work as a chef and cookbook author—took on a sharp, but new, focus. That image of the grocery store’s perimeter made me realize that the whole range of natural fruits, vegetables, grains, meats and fish have had nutritional staying power. In contrast, the recommendations of my nutritionist colleagues reflect—shall I say it?—a rather fledgling approach to the relationship between food and the human body. Though I admire the nutritionist’s scientific approach, theirs is a new science, only having been around for 130 years or so. Beginnings are always fraught with regular “revolutions” in understanding.

The more mature perspective, it dawned on me, comes from traditional cultures that trace their roots back to antiquity. The traditional ways of eating, say, in the Mediterranean or Mexico, in China, Thailand or India. These are gastronomical approaches to nourishing large groups of people that were developed over millennia, that focus on delicious flavor, and that have stood the test of time. Though not developed based on a scientific model, they exemplify what works for (and satisfies) the culture that developed it—day in and day out.

Now, I’m not talking about isolated dishes in these cuisines, but rather the whole kit-and-caboodle of how a culture eats from morning to night, weekday and weekend, festival and famine. That’s where we discover the nutritional wisdom a culture has developed over centuries. With anything less than the whole picture, we run the risk of skimming off luxuriously rich dishes from other countries without including the simple preparations cooks of those countries use to balance them.

It’s telling that if you remove from the world’s traditional cuisines any influences of Western fast foods or industrialized or prepared foods, most of them have developed more-or-less the same approach to nourishment—the grocery store-perimeter approach. They focus on a variety of simply prepared fresh foods. Modest amounts of deliciously seasoned food that balance the complex carbohydrates of fruits, vegetables, grains and legumes. Nothing processed, all of it “low on the food chain” (as in “natural, unprocessed”), with modest amounts of meat and fish, and just a few sweets.

But a few days of that is enough, from most cultures’ perspective. Human beings have a need to blow off the top—to feast, to party. Regularly. Big hunks of meat, dynamic music, lavish preparations, refined anything, luxuriously rich sweets. Even if it’s just a feasting celebration of the weekend’s arrival, abundant unique dishes seem even more special because of the simplicity of everyday nourishment.

It’s that feasting our scientific approach to nutrition hasn’t embraced yet. We put ourselves on diets (I think we can admit it: they’re bleak diets) that lead us to judge everything we put in our mouths as “good” or “bad,” that cause us to say that a break with their dietary proscription is “cheating.”

Where does that come from? A blind faith in the wisdom of the relatively young field of modern nutrition? A Puritanical heritage? An information overload that leaves us grasping for a couple of simple scientific principles we can hold on to?

Whatever the source, the fact is that we haven’t been able to tackle the age-old simplicity of feasting. We’ve allowed the feasting-as-essential-to-good-health approach to be swept into the same dust bin with malnutrition and poor sanitation.

But that’s just wrong. And we all know it…in our guts. So, many of us just eat defiantly. Willy-nilly and all the time. To the point that we’ve become the fattest people on earth.

Essential Learning #5: The world’s most time-honored cuisines illustrate that (1) everyday eating is best kept to deliciously seasoned, simple preparations of natural ingredients (mostly unrefined and balanced between a variety of fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes and meat) served in moderate portions; and that (2) fabulous feasts—once a week, or, on special occasions, more—are an essential part of our healthy nourishment.

To say it another way, cuisines that have healthily nourished generation after generation have a pretty brilliant—but basic—way of putting essential foods together in the right proportions for everyday eating. Call it their foundation dishes. But those same cultures also realize that feasting is essential for a culture’s aesthetic development, encouraging cooks to reach for new culinary heights. And that feasting is essential for cultural unity, bringing groups of people together around the table to share sustenance, culinary art, related histories. And that feasting is essential for the health of our bodies, allowing us the satisfaction of feeling thoroughly, completely full—with no need for midnight Haagen Dazs raids.

A feast can make our spirits soar for days, while our bodies are regenerating themselves on everyday fare. In other words, no one ever got fat on a weekly feast, but missing that feast can leave you with strong cravings (both physical and spiritual) all week long.

Who can resist a strong craving?

* * * * * * *

I’d figured out how much food my body needed to maintain a weight that made me feel comfortable. I’d paired away calorie-rich processed foods (and extraneous stuff—like soda and cream in my coffee—that I didn’t really care all that much about) to allow me to eat more of what I really liked. And I’d gotten full swing into weekend and special-occasion feasting (noting that no matter how big the weekend feast, my weekly weigh-in stayed just about the same.)

I should have been totally satisfied, having found an equilibrium for myself, but a little fact of nature kept rearing its head to mock me. I knew that as each year passed, I lost a pound or so of muscle tissue. That’s the fact of nature…of aging.

Now, to some, that may not sound like a very big deal. Until you realize that muscle tissue (for most of us) pretty much gets replaced pound for pound by fat … and fat requires much less fuel (read: calories) to maintain than the muscle does. Meaning that each year, to maintain my optimal weight, I would need to eat less. And that was a bummer. I wanted my cake and eat it to, so to speak. To maintain my weight and be able to eat the same amount I was enjoying.

Being completely bummed out by nature’s unfairness came about the time I decided I wanted to learn the yoga pose called forearm balance. Forearm balance is a little like a hand stand, except that you perch upside down balanced on your forearms—like a sphinx with his legs straight up over his head. I just didn’t have enough strength, and I knew it would take months—years?—of practice to develop it.

I found something so compelling about yoga inversions—head stands, hand stands and the like—that I was determined to master this one. I loved the freedom I felt in this flip-flopped, gravity-defying position.

So I bought some dumbbells, read some articles on strength training, and made a resolution to augment my yoga with just the strength exercises I’d need to sustain that inspiring posture.

My shoulders and arms responded immediately and before I knew it, I was hovering in forearm balance and understanding a counter-fact of nature: I could maintain (even grow) muscle tissue by strength training, kind of reversing the flow of nature.

Well, I was feeling great—stronger, more energetic, confident (I could do forearm balance for goodness sake!). And I was really hungry. I hadn’t planned on that. Hungry as in starving. I’d read a lot about strength training—how the aficionados ate five or six meals a day, how they focused on a balance of protein, complex carbohydrates and fats for optimal muscle growth. I’d memorized their motto cold: you can’t grow muscle without good food.

Strength training was for me. Not only did I feel and look great, but the muscle I was growing (and not losing) was asking me/encouraging me/requiring me to eat more. This was the perfect exercise for a food lover. And as the strength training enthusiasts point out, muscle burns fuel all day long—as opposed to the more limited fuel-burning potential of aerobic activities like jogging (definitely not for me) or treadmills or Stairmasters (I’m already bored). Through the millennia, it seems, our bodies have become accustomed to some pretty rigorous, muscle-requiring work.

Essential Learning #6: To be able to enjoy great food without gaining weight, our bodies need to burn as much fuel as possible. Though aerobic activity burns fuel, strength training offers more: more strength, better appearance, and more every-minute fuel-burning muscle.

There you have the six essential learnings of my past half decade. I would never presume that they’ll be perfect for everyone, though many of them will. Because they can (in fact, must) be personalized as each of us discovers our perfect balance of food (varieties and quantities) and physical activity. That may be disappointing to some of you—no 14-day plan to loosing 30 pounds, no 30 days to a cover model’s body—but it’s real life. All you have to do is listen to the truths your body and spirit can teach you.

A Snapshot of My Everyday Activity and Eating

Though I work evenings, I’ve always been an energetic early riser, making getting enough sleep (my body and psyche need at least 7 1/2 hours for healthy functioning) a challenge. First thing, I engage in physical activity to focus all my energy and allow my mind to distill thoughts and ideas (I always have a pad around while I’m working out). Three days a week I do a vigorous yoga practice, and three days a week I do strength training—usually for 45 minutes to an hour. One day I rest completely—and every few months I take a whole week off.

After that, I have breakfast with my family—yogurt and fruit (in winter I usually make a smoothy with frozen berries) or oatmeal or granola and juice.

Midmorning I’m always really hungry, so, when I’m tasting all the lunch-time preparations at the restaurant, I eat a snack—a small bowlful of nuts; a taco of beans, cheese and salsa (and sometimes chicken or some leftover meat preparation) on a corn tortilla; and usually a little fruit. (If I’m away from home, I always carry whole grain snack bars to get me through until lunch—though I don’t consider them “natural” enough to be part of my everyday eating.) I think of snacks as mini-meals, combining a variety that includes a little fruit or vegetable, a little grain or bean component (for complex carbohydrate) and some kind of dairy or meat (for protein) since protein helps me feel fuller longer.

Between 1:30 and 2 p.m., I have lunch: My wife, Deann, and I sit down and order right off our restaurant’s menu, typically sharing one or two appetizers (most of our appetizers focus on vegetables and greens) and an entrée (ours are pretty hearty), occasionally two entrees. That’s when I really think about how hungry I am and consciously consider how much to eat of what’s on my plate. I feel best when I have a larger lunch and a smaller dinner.

At 5 o’clock I’m back tasting all the dinner preparations (there’s usually 40 to 50 things to evaluate, refine, re-season—from soup to dessert). So that’s my afternoon snack. I’m always less hungry than at mid-morning, so I’ve learned to just taste through all the sauces and soups and snack on a little of the grilled chicken we shred into tortilla soup (or snack on red chile lamb stew or shredded pork picadillo or ceviche) and salad and rice or beans. I’m well known for having a huge sweet tooth, and my afternoon snack always includes a spoonful or two from the dessert station—ice cream, a fruit tart, whatever dreamy thing our pastry chef has created.

Because of my business, I eat dinner late, usually around 9:30 or 10. It’s usually replay my approach to lunch: an appetizer or two or an entrée if I’m by myself, the lunch sharing routine if I’m with my wife. I am never as hungry at dinner as I am at lunch, so I find myself leaving more of our normal restaurant portions on the plate. If there’s a dish I really want to eat, but know I can’t finish it, I’ll ask the chefs to divide it on two plates, so I can offer a taste to cooks, hosts or servers.

I know it sounds idyllic, having all those sumptuous choices for meals and snacks. The blessing of being a chef. And also the curse, since the variety and abundance could seduce anyone into never saying “Stop!”

Over the last few years, I’ve focused on learning my everyday, healthy balance within all this deliciousness. Rather than categorizing the foods around me as “good” foods to rely on exclusively and “bad” ones to avoid, I’ve learned the proportions in which I can enjoy all great food and stay optimally healthy.

And what do I do when the restaurant’s abundance is out of reach—when I’m cooking at home? I have a stash of simple, thoroughly delicious, multi-cultural recipes that I can throw together quickly, that are flexible enough to allow me to incorporate a variety of ingredients, and that make enough quantity for me to snack on the next day.

Frontera Kitchens: Restaurants

Rick and Deann Bayless offer a taste of their passion for Mexico in Chicago at the casual Frontera Grill (opened in March 1987) and the dressier Topolobampo (opened in November 1989).

Frontera Grill and Topolobampo have led the way in a national awakening to the breadth and refinement of authentic Mexican cooking. In addition to uniform acclaim from local and national press, Frontera and Topolo have received the coveted Ivy award (1991) and the Mobil four-star rating. Patricia Wells, writing for the International Herald Tribune, selected Frontera in 1994 as the world’s third best casual restaurant, after her year-long international journey.

Topolobampo was chosen by Esquire as one of the top new restaurants in America in 1991, and is the first ethnic restaurant to receive 4 stars (out of 4) from Chicago magazine. In 1999, Restaurants and Institutions honored it with another Ivy Award. The restaurants’ wine list has received the Wine Spectator’s Award of Excellence since 1990. In 2001, Topolobampo was selected as one of America’s Top 5 Restaurants for Outstanding Service by the James Beard Foundation.

https://web.archive.org/web/20021017080600/http://fronterakitchens.com:80/restaurants/

Chicago Magazine, July 2001: Topolobampo – 4 stars by Rick Bayless

Who would have thought? Who—in an ethnically staunch Mexican restaurant—would have aspired?

For the last 12 years, we’ve been cooking at Topolobampo not so much to capture stars as to capture the vitality, generosity and guileless sophistication of true Mexican cooking. We’ve cooked dishes that stole my heart while I was studying Latin American culture in Mexico, while I was researching that country’s regional cuisines for cookbooks and articles, while I was there celebrating milestones in my and my family’s lives. We’ve cooked dishes inspired by our thousands-strong Mexican cookbook collection, some dating back to the early 1800s. We’ve cooked dishes that virtually leaped into being at our stoves, informed by Mexican tradition but made deliciously tangible with seasonal, sustainably raised food from our extensive network of local farmers.

I’ll admit, however, that a single Mexico City meal was almost single-handedly responsible for fueling these years of Topolobampo aspiration. Student-poor, my wife, Deann, and I rode a bus south down Insurgentes from our mid-town quarters to a tony enclave called San Angel. There we found San Angel Inn. Set among the lushness of gardens that had never known the ravages of frost, this ex-hacienda cum restaurant offered a luxurious moment of tranquility to take in (both literally and figuratively) the deeply rooted tradition of Mexican cooking and eating. Perfect picadillo-stuffed chiles rellenos and pork loin in long-simmered red-chile adobo; hammered copper chargers and hand-painted plates; wine from Santo Tom’s in the Valle de Guadalupe, Baja California. It was an unforgettably multifarious experience, a gustatory symphony played in perfect harmony–comfortable surroundings, richly complex flavors, gracious people.

That’s the piece we’ve spent years rehearsing for our restaurant guests. Sure, critical acclaim brings enormous satisfaction, but it has never meant as much to me as hearing guests exclaim that our flavors–our place–sang with the soulfulness they’d only known at an abuela’s (or tia’s) house in Puebla or Veracruz or any other Mexican town.

Frontera Staff Trip: Michoacan

It had been ten years since we’d visited Mexico’s western state of Michoacan, just south of Jalisco, the land of Guadalajara and Tequila. One of Mexico’s most beautiful, well-developed states, Michoacan is famous for (at least) four things: incredible colonial architecture (Morelia, the capital, and Patzcuaro are both UNESCO World Heritage Sites), folk crafts (all the copper-work in Topolobampo comes from there), sweets (made from fruit and from caramel) and avocados.

It had been ten years since we’d visited Mexico’s western state of Michoacan, just south of Jalisco, the land of Guadalajara and Tequila. One of Mexico’s most beautiful, well-developed states, Michoacan is famous for (at least) four things: incredible colonial architecture (Morelia, the capital, and Patzcuaro are both UNESCO World Heritage Sites), folk crafts (all the copper-work in Topolobampo comes from there), sweets (made from fruit and from caramel) and avocados.

We delved into all of it, but the highlight of our trip was our visit to the Bautista’s idyllic avocado farm near Uruapan. Our vans ambled over unpaved country roads through misty, lush valleys filled with avocado and macadamia trees, past trout ponds and dairy cattle pastures until we reached a clearing with a large, open-air packing shed. As thirty-some of us piled out of the vans, a group of mariachis blared a welcome and the heavens opened. From underneath the shed’s roof, the rain-drenched swath of nature looked even more like Eden—with a slightly scratchy mariachi soundtrack.

Clothed tables were set with smoked salmon trout from the ponds (with, of course, a somewhat combustible, mayonnaisy manzano chile salsa). We were offered guacamaya cocktails—a lime-avocado-tequila concoction that seemed better the more tequila you added. Most of us asked for Bohemias or Coronas, too.

Just when we were about to settle into our trout-in-macademia-brown-butter entrée, Alejandro Bautista barreled up in his muscley pickup. He cracked open a bottle of mezcal from San Luís Potosí (his favorite) and launched into an hour-long rhapsody for the avocado (“I love my wife, but I L-O-V-E avocados”). We were totally enraptured, as he took us from his father’s planting the first of his 200 acres of avocados back in ’65, to the virility-inducing qualities of his favorite food (whose name, by the way, means “testicle” in Aztec). We asked him about ripeness (it takes a full year for an avocado to mature on the tree, but it won’t get soft-ripe until after it’s picked), about varieties (they only grow the all-around-beloved Hass) and about the possibility of getting their meticulously raised avocados in our restaurant (hope, pray).

The trout was as spectacular as the setting, just slightly less inspirational than Alejandro’s words. And the mariachis, who we suspected had had a few Coronas before we’d arrived, played for hours. It was the first time any of us had ever seen the leader of a mariachi band sit down while singing. Or smoke while singing, for that matter. Jane Alt’s exquisite photos from the trip are on display at Frontera. RB

Topolobampo Menu, July 15 – August 9, 2003: A menu inspired by our 2003 staff trip to Michoacan

As we reach the peak of the growing season, every dish is all about the bounty of local ingredients. Heirloom tomatoes, spicy green chiles, and sweet tomatillos, to name a few.

Tracey Vowell, Managing Chef

ENTREMESES

Aguacate Sin Parar – luscious molded avocado cream (infused with roasted garlic and herbs, topped with quail eggs and American spoonfish caviar) with avocado-poblano-jícama salad, tangy arugula and a zesty avocado-tomatillo drizzle. 9.75

Camarones en Chile Negro – aromatic crispy fresh shrimp in a pool of robust pasilla chile broth studded with favas, organic peas and cactus. 9.50

Salmón Curtido, Salsa de Chile Manzano – thin-sliced home-cured wild Alaskan salmon drizzled with creamy manzano chile salsa, sprinkled with olive-parsley confetti. 9.50

Uchepos Clásicos – fresh corn tamales (steamed in corn husks), nestled into braised wild greens and drizzled with spicy arbol chile salsa and homemade thick cream. 9.50

Churipo de Lujo – red-chile brisket soup studded with grilled zucchini, Napa cabbage and crispy beef. 8.50

Sopa Azteca – dark broth flavored with pasilla chile, garnished with grilled chicken, avocado, melting cheese, thick cream and crisp tortilla strips. 8.50

Ensalada Topolobampo – Topolo salad of young organic greens with cilantro, garlic croutons and dry Jack cheese, in lime-serrano dressing. 8.50

PLATILLOS FUERTES

Carnitas de Chuleta – lime-marinated, slow-cooked Maple Creek pork chop carnitas with heirloom tomato salsa, all-green guacamole and crispy potato cakes. 28.50

Pollito a la Plaza – Pátzcuaro-style Swan Creek rock hen with red-chile enchiladas, seared potatoes and carrots, crunchy garnishes (tangy Napa cabbage, pickled jalapeños, crispy onions and cilantro), homemade fresh cheese and a drizzle of thick cream. 28.50

Conejo en Salsa de Huitlacoche – Gunthorp Farm rabbit (braised leg, herb-roasted loin) in roasted tomatillo sauce infused with earthy huitlacoche (corn mushroom) and smoky morita chiles; served with classic Mexican white pilaf and garlicky braised greens. 28

Birria de Chivo Estilo Apatzingan – slow-roasted Swan Creek Boer goat marinated with guajillo chiles, roasted tomatoes and orange; served with rich pan juices, runner beans and ribbon salad. 28.50

Corundas Rellenas – classic Michoacan triangular tamales filled with homemade herby fresh cheese and served with chilaca chile cream, roasted peppers, oyster mushrooms and greens. 20

Trucha Empapelada – garlicky, herby, chile-infused Rushing Waters rainbow trout roasted in parchment paper with fingerling potatoes, thin-sliced patty pans, shiitake mushrooms and flatleaf parsley; served with spicy “chilaquil batido” salsa. 28.50

Callos de Hacha en Mole Verde Michoacano – pan-seared, diver-caught sea scallops in Michoacan-style green mole (tomatillos, sesame, pepitas, serrano, herbs) with green chile rice, grilled summer squash and garlic chives. 28.50

CHEF’S TASTING DINNER:

5 courses for $70

(with 5 perfectly matched wines, add $35)

Meet the Staff

https://web.archive.org/web/20081121201109/http://dev.rickbayless.com/restaurants/staff.html

Frontera 20th Anniversary Party

A great time was had by all at our recent 20th Anniversary Party. Chef Bayless teamed with special guests Enrique Olvera of Mexico City’s Restaurante Pujol and winemaker Andrew Murray to create a memorable 4-course meal. Afterward it was party time in the big tent with Angel Melendez Tropical band, Lucha Libre masked wrestlers, and tasty Mexican treats.

https://web.archive.org/web/20070728003936/http://www.rickbayless.com/about/notebook/20_party.html

The Growth Process, by Rick Bayless

My parents were my first restaurant mentors. At the Hickory House, our family’s barbeque restaurant in Oklahoma City, they made sure I recognized the importance of freshness. Freshness of the food, of the look of the place, of the staff. They taught me that a restaurant needs to look like it’s just opened, while giving the impression that it’s been there forever.

Constant change, growth and improvement were their freshness secrets, and I’ve striven to walk in their footsteps: Frontera in 1987, Topolobampo in 1989, a daughter in 1991, Zinfandel Restaurant in 1993, a new book and product line in 1996, and a new, improved, expanded Topolobampo and bar area in 1997.

That last one might sound like enough to tackle in one year, but it hasn’t been my greatest challenge. My garden has.

After 20 years doing container gardening in apartments (much of it on a 17th floor terrace overlooking the lake), we moved to a big Bucktown lot. A thousand square feet in flowers, a thousand square feet in vegetables. All organic. While I can’t say it’s been easy, it sure has been satisfying, and humbling.

You’ve been eating my mesclun mix, chard, amaranth greens, squash blossoms, radishes and herbs. Well, mine and Mother Nature’s. She decided not to be forthcoming with runner beans or tomatillos, and for some reason, she let loose squash borers to cut short the blossom season. I could buy pesticides, insecticides and chemical fertilizers and be done with it. Or I can continue on my sustainable, education-intensive path to achieving the perfect natural balance in my garden. I never liked the easy way.

Besides a more-than-healthy respect for nature, I’ve gained a massive appreciation for organic farmers — the kind all farmers were before the advent of chemical solutions. They are some of the smartest people on the planet.

Staying Local, by Tracey Vowell

How many local farmers do you know? Not the ones that are growing commodity grains and feed for animals, but the ones that are working to improve our food supply, the ones that are working to preserve genetic diversity and to recreate that sense of community that has become so elusive in recent times. As a restaurant, we have worked diligently for years to develop direct relationships with farmers, committing ourselves to using their produce consistently, and establishing long-term arrangements for the production of some of our more exotic ingredients. All of this effort secures the achievement of two goals: to support local businesses, especially agricultural efforts, and to secure the best possible ingredients for you, our guests.

How many local farmers do you know? Not the ones that are growing commodity grains and feed for animals, but the ones that are working to improve our food supply, the ones that are working to preserve genetic diversity and to recreate that sense of community that has become so elusive in recent times. As a restaurant, we have worked diligently for years to develop direct relationships with farmers, committing ourselves to using their produce consistently, and establishing long-term arrangements for the production of some of our more exotic ingredients. All of this effort secures the achievement of two goals: to support local businesses, especially agricultural efforts, and to secure the best possible ingredients for you, our guests.

Now, as a result of our effort, we have a veritable deluge of ingredients available to us, each in its appropriate season, produced locally by people that have, in their own way, become part of the Frontera Family.

The next time you are dining at Topolobampo or Frontera Grill, look for the names of our local producers on the menu. Maple Creek pork, Crawford lamb, Gunthorp chickens and ducks, Swan Creek boar goat, Steve Grebb’s garlic. That just starts the list. Knowing where your food comes from is the first step to answering, How many local farmers do you know?

Wines of Baja, by Jill Gubesch

Rick and Deann Bayless, Carlos Alferez (our general manager-partner) and I headed south from San Diego during the first week of August for a remarkable adventure into Mexico’s wine country. That’s when they celebrate the Fiesta de la Vendimia (Wine Harvest Festival), complete with open-air concerts at the wineries (we saw Willie and Lobo at Chateau Camou), winery tours, street fairs and a grand finale paella cook-off with over a hundred entrees.

Rick and Deann Bayless, Carlos Alferez (our general manager-partner) and I headed south from San Diego during the first week of August for a remarkable adventure into Mexico’s wine country. That’s when they celebrate the Fiesta de la Vendimia (Wine Harvest Festival), complete with open-air concerts at the wineries (we saw Willie and Lobo at Chateau Camou), winery tours, street fairs and a grand finale paella cook-off with over a hundred entrees.

Baja California’s Valle de Guadalupe is Mexico’s main wine region. It’s a valley located about six miles north of Ensenada and about 15 minutes from the Pacific. The largely east-west orientation of the valley combined with the ocean influence provides cool evenings balancing the warm days for optimal grape growing conditions.

The southern portion of the Valle de Guadalupe is designated as the Valle de San Antonio de las Minas, which is closer to the Pacific with cooler growing conditions. The wine grape harvest is two to three weeks later there than in the northern part. The other two nearby grape-growing valleys include the Valle de Santo Tomás (30 miles south of Ensenada) and the Valle de San Vicente (23 miles further south from Santo Tomás).

Of the wineries we visited, the most impressive was Monte Xanic. The winemaker, Hans Backoff, founded the winery in 1988 and is at the forefront of producing topflight wines in Mexico. He is constantly striving for (and reaching) better wines with each vintage. And he’s a wonderful host, inviting us to have lunch with him (classic—if a little heavy—northern Mexican specialties) overlooking the vineyards. We didn’t even complain that the air temperature was over 100º, especially since he invited us for a dip in the winery’s swimming pool before we ventured on our way.

Among our other stops, we had a brief, but thoroughly impressive, visit to Adobe Guadalupe Vineyard, a relatively new, award-winning winery located a short distance from Monte Xanic. Tru and Don Miller own the beautiful property (they run it as a rather luxurious bed and breakfast), while Hugo d’Acosta is the winemaker. He also makes wine at his own property, Casa de la Piedra. Both labels are among the best of the area. We were able to sample most of the area’s wines as we tasted the paellas at the cook-off. Bodegas de Santo Tomás, Casa Pedro Domecq, Mogor-Badán, Chateau Camou and Liceaga added to those we’d already tasted.

We are working diligently towards bringing you the full array of Baja California’s amazing premium wines at Frontera/Topolobampo—hopefully within the next year. Keep your eyes on the wine list. ¡Salud!

For more information on the wines of Baja California, we recommend Touring and Tasting Mexico’s Undiscovered Treasures by Ralph Amey.

Guide to Classic Mexican Food & Wine

Wine offers more thrilling complexity than any other beverage — more intricate layerings of aroma, more diversity of flavor, more spirit. Which means wine is absolutely the perfect match for the complex, varied dishes Mexico’s classic cooks have turned out for centuries. Here’s our insider’s guide to classic Mexican flavors and wines that harmonize with them.

Rick Bayless, Executive Chef

Jill Gubesch, Sommelier

Easy Does It, by Rick Bayless

There was a time in my life, just after graduate school, when I hosted “competitive dinner parties.” Perhaps that rings a bell for you, too: the guests arrive at 7 p.m. or so; you pass around an array of dazzling, exotic hors d’oeuvres (as we called them then); an ultra-impressive three-course dinner begins at around 8:30; and everyone goes home with stars in their eyes at 11 or 12, leaving you flat-out exhausted. Those dinner parties were an amazing amount of work – I remember a week or more of planning and prep cooking – and the kitchen-centered tension was, I believe, of Olympic proportions.

There was a time in my life, just after graduate school, when I hosted “competitive dinner parties.” Perhaps that rings a bell for you, too: the guests arrive at 7 p.m. or so; you pass around an array of dazzling, exotic hors d’oeuvres (as we called them then); an ultra-impressive three-course dinner begins at around 8:30; and everyone goes home with stars in their eyes at 11 or 12, leaving you flat-out exhausted. Those dinner parties were an amazing amount of work – I remember a week or more of planning and prep cooking – and the kitchen-centered tension was, I believe, of Olympic proportions.

No more. Today, dinner with my family and friends is one of my most relaxed, favorite times. I want nothing to get in the way of our fun together, especially anxiety about what we’re eating.

But don’t get me wrong. We’re not dumping take-out containers into pretty bowls. No, we’re serving great, fresh food – with a little help from our friends. I’ve learned to pare back my offerings, to make everything simple, dramatic and great tasting, and to involve everyone in the activities. Get the kids washing, spin-drying and tossing a simple salad (a simple dressing is within most kid’s reach). Adults can chop and stir and grill–whatever. Just be prepared when they arrive. Here are my tips:

Choose easy, tasty dishes and not too many of them. Think about dishes like a brothy, boldly flavored vegetable soup followed by one-pot dishes (braised pork loin with roasted tomatillos and white beans is a favorite). Marinated roast chicken is a hit with a salad of roasted vegetables, or with side dishes like jazzed up mashed or scalloped potatoes.

Buy the best, freshest ingredients you can – from a farmer’s market if possible. (Letting the ingredients impress your friends can relieve finished-dish anxiety). Have all the ingredients and any special cooking equipment at easy access.

Think through who’ll be best for what tasks before your guests arrive. Some folks love cooking, others will be happy to hang out, chat and peel potatoes or wash pots. Don’t forget to plan something for kids to do, so everyone feels they have a hand in the preparations.

Have beverages and munchies out when folks arrive so no one feels famished while dinner’s being made. Unless the garden’s in full swing, allowing me to offer cut-up, just-picked vegetables, I purchase the munchies–things like olives, nuts, chips, pita “chips” and, sometimes, dips.

Unless the dessert is very, very simple, make it before everyone arrives (desserts usually require the most concentration). Or, if time’s just not on your side, buy a nice dessert or part of the dessert. One of my favorite, fast, half-homemade desserts is grilled bananas (I put them on the grill while we are eating dinner) and serve them with store-bought ice cream and a drizzling of cajeta (Mexican goat-milk caramel sauce) we can buy at a Mexican grocery.

Some of the best times I’ve had with friends have been kitchen times. That’s what led me to plan in cooking time with everyone. Cooking breaks the ice, dispels the worry. Cooking together means everything’s easier for me, more fun for the guests. Perfect for the way many of us live these days.

¡Buen provecho!

Style: Candleholders, by Rick Bayless

Light, especially the warming golden glow of candlelight, is, I find, one of the most sustaining elements in the rather gray skies of Chicago, where I live. I’ve brought home dozens of candle holders from Mexico (most of them made by marketplace artisans who, understandably, have not concept of standard American candle-sizes), and through the years I’ve weeded out all but a few of the most beautiful and most practical. Those are the ones I’m drawn to mostly for special occasions’ for everyday candlelight I turn to simpler, easier and less-expensive alternatives.

When I’m in Mexico, I go into the market and buy the little votives (the small candles that are poured into facetted glass cups—the ones most commonly taken as prayer candles into the churches). They’re inexpensive (as little as three for a dollar), and, when the candles burn down, they can be replaced by tea lights or little holder-free votives. The little glass votive holders, by the way, serve another purpose: they make pretty cool shot glasses for tequila or mezcal.

At Hacienda Hardware 707-963-8850;Haciendahardware.com in California’s Napa Valley (Rutherford), as well as in other places, you can buy wonderful old wooden sugar molds (used for making piloncillo, Mexico’s raw sugar). They’re long blocks of wood with conical indentations (for molding the sugar) bored into the top. Stand small pillar candles in the indentations and you have an impressive warm display. Hacienda Hardware sells an aluminum reproduction on their web site.

Sundance catalog sundancecatalog.comsells a modified wooden reproduction of the piloncillo mold that’s perfect for little tea lights—practical, if not as rustic or beautiful. But they also sell a wonderful 9-compartment basalt (lava-rock) holder for tea lights that creates an unforgettable mid-winter glow in the middle of your dining table. Though it’s not from Mexico City (they’re made in Southeast Asia), the materials and craftsmanship are in perfect harmony with my otherwise Mexican-inspired table.

Cooking Techniques: How to Roast Fresh Chiles

Chef Rick Bayless prefers to roast large fresh chiles like poblanos over a charcoal or wood fire because he thinks that’s the way they taste the best. We’ll admit it’s impractical, however, in January in Chicago. Our second choice is to roast them over the flame of a gas burner. Third choice is to roast them close up under a very hot broiler. With this method, the flesh of the chile tends to cook more than we like before the skin blisters, because most home broilers aren’t nearly as hot as the grill or the flame.

Chef Rick Bayless prefers to roast large fresh chiles like poblanos over a charcoal or wood fire because he thinks that’s the way they taste the best. We’ll admit it’s impractical, however, in January in Chicago. Our second choice is to roast them over the flame of a gas burner. Third choice is to roast them close up under a very hot broiler. With this method, the flesh of the chile tends to cook more than we like before the skin blisters, because most home broilers aren’t nearly as hot as the grill or the flame.

The reason we roast chiles at all is to cook the flesh a little (cooked chile tastes less grassy), to rid them of their tough skins and to add a touch of smokiness. Large fresh chiles require a bit of vigilance during the roasting process: you want to evenly char—really char—the skin without turning the flesh to mush. That means a very hot fire and frequent turning.

Many cooks tell you to put roasted chiles in a plastic bag and let them cool before peeling. Trapping all that heat means almost certain overcooking, so Rick recommends putting them in a bowl and covering them with a towel for a few minutes. The steam they release will loosen the skin, making them easier to peel.

Most small chiles, like serranos and jalapeños, are roasted directly on a dry skillet or griddle (or on a grill or in the fire, if those are options) turning them until they’re soft and irregularly charred. Small chiles are rarely peeled after roasting.

Most small chiles, like serranos and jalapeños, are roasted directly on a dry skillet or griddle (or on a grill or in the fire, if those are options) turning them until they’re soft and irregularly charred. Small chiles are rarely peeled after roasting.

Don’t hestitate to roast (and peel) fresh chiles a day or two ahead; they keep well in the refrigerator. Lots of cooks, especially in the Southwest where large chiles are grown, like to roast a lot of chiles at once and freeze them; the practice in vogue seems to be freezing the roasted chiles with the skins on; peeling them when defrosted seems to preserve flavor and texture.

Iron Chef America: Rick Bayless vs. Bobby Flay

Challenger Rick Bayless faced off against Iron Chef Bobby Flay in the season premiere of Iron Chef America on Food Network (Sunday, January 16, 2005). The Kitchen Stadium battle pitted these two culinary titans against the clock and each other to create a five-course tasting menu using a special mystery ingredient. In case you missed it, our man got buffaloed.

Top Chef Masters Finals blog

Top Chef Masters Haiku Contest

How to Reheat Tortillas

The best corn tortillas, of course, are those that still retain the heat of their original griddle-baking: they’re supple, toasty smelling and earthy tasting with an almost meaty texture. These (almost) whole grain goodies have no added fat, which makes them very healthy. Once they cool, though, they dry out rather quickly and turn stale (like real French bread).

Making tortillas for every meal isn’t practical for most of us, however; neither is running to the local tortilla shop just before sitting down to dine, as many do in Mexico. That leaves reheating packages of lifeless, factory-made corn tortillas. There is a difference between ones that come from small factories and the mass-produced tortillas you find in the refrigerated food cases. (Some of the latter are not made from masa and won’t ever be very good.) Cold, any corn tortilla is like dry meal in your mouth, but steam heating is an effective way of bringing back tender suppleness. Following are my favorite ways of rejuvenating corn tortillas:

Steam-heating a Small Amount of Tortillas: Set up a vegetable steamer in a pot filled with about 1/2 inch of water. Cover and bring to a boil. Wrap 1 dozen tortillas (you can push it to 15, but no more) in a heavy (preferably terrycloth) kitchen towel. Place over the boiling water in the steamer, cover with a tight lid,time 1 minute, turn off the heat, let stand without opening the lid for 15 minutes and they’re ready to eat. If you place the whole contraption in a low oven (not over 200 degrees), you can keep them warm for an hour or so.

Steam-heating a Large Amount of Tortillas: Set up a rack in a large roasting pan, pour in about 1/2 inch of water and cover the rack with a heavy (preferably terrycloth) kitchen towel (it shouldn’t touch the water or it will act as a wick, soaking the bottom layer of tortillas). Divide your tortillas into stacks of 10 or 12 over the cloth, cover with a second cloth, cover the pot tightly and bring to a boil over medium-high heat. Time 1 minute, turn off the heat and let stand 15 minutes without opening the lid. You may put the roasting pan in a low oven (not hotter than 200 degrees) and keep the tortillas warm for about an hour or so. Plan to heat a few extra tortillas that you’ll need, since the top and bottom ones reheated by this method tend to get so soft they fall apart.

Other Reheating Methods: Factory-made tortillas packaged in the paper wrappers (they may have a thin plastic-like coating inside) may be successfully reheated in a microwave oven: make a tiny hole in the package (to let steam escape), then microwave in the package for 30 to 60 seconds (depending on the power of your oven) on high. Wrap in a heavy cloth and let stand a few minutes before serving.

When you’re just reheating a few tortillas (or if you’re in a hurry), moisten your hands with water, rub those damp hands across the tortillas you’re going to reheat, then lay a stack of 4 on a griddle heated over medium. Flip them every few seconds, shuffling the deck from time to time, until all four are soft and hot (the water helps create a little steam, the stacked effect ensures that they will heat more slowly without letting the internal steam evaporate quickly.) Wrap in a heavy cloth and serve.

If your tortillas are relatively fresh, you can either heat them one at a time on a hot griddle or over a medium open flame, such as a gas burner, turning them every few seconds until hot and a little toasty (total time on the griddle or flame is about 15 seconds). This adds a hint of crispness to the tortilla, unless its stale and dry to start with, in which case the tortilla will become even more inedible.

Keeping Tortillas Warm for Serving: Tradition dictates a (usually uncovered) basket (chiquihuite is the word for the proper basket in Mexican Spanish) lined with a cloth for holding just-made tortillas. When they come off the griddle, those little corn cakes are so hot that a stack of 20 can stay warm for nearly an hour if the cloths are heavy and the basket tightly woven. A styrofoam-like, covered “tortilla warmer” is environmentally a bad idea, though practically it does a great job; they keep tortillas warm for more than an hour, as will several other insulated or thermal containers that have hit the market.

A small basket lined with a cloth is the nicest way to keep tortillas warm at the table, though there are many small modern insulated containers (we use a little red plastic one at Frontera) that do the job nicely.

Frontera’s Mexican Chocolate Pecan Pie Bars

Note from Rick

Q&A with Rick Bayless

Q: What got you interested in Mexican food?

A: You mean how does a gringo who grew up in an Oklahoma barbeque restaurant end up with two popular Mexican restaurants in Chicago? Well, I grew up in a food family, and food had always been one of my passions. The other came with a trip to Mexico when I was 14. Mexico was relatively close to Oklahoma City, but to me it sounded about as exotic and faraway as I could get. I fell in love with Mexico on that trip and just kept coming back for more. I’ve never stopped exploring Mexico.

In terms of food, certainly the regional variety, the complexity and nuance of authentic Mexican dishes both surprised and impressed me. But I also wanted to share this amazing culture I was discovering. And I think one of the best ways for people to communicate is through food. That’s what got me researching my first cookbook and eventually led to opening the Frontera Grill and, later, Topolobampo.

Q: Mexican restaurants are popular in the U.S., but people don’t often think of cooking Mexican cuisine at home. Why the difference?

A: Unfortunately, I don’t think a lot of people have ever understood Mexican as a cuisine. They typically think of a few simple dishes that have been adapted and popularized in the States, in some cases entirely created here. But the funny thing is, you’d be hard pressed to even find burritos, fajitas and nachos in most of Mexico. The real food of Mexico can be a revelation. When people taste the classic flavors found in moles, barbacoas, ceviches and adobos, they start to appreciate that Mexico has some incredible contributions to world cuisine. Then they want to start trying some of those flavors at home.

As far as home cooking, it’s not unlike where we were 25 years ago with Italian cooking. Back then it was pretty much spaghetti and meatballs. Today we’re making our own pesto. I’d say Americans are still at the “spaghetti and meatballs” stage as far as our familiarity with Mexican cuisine.

Q: Your recent book has been one of the best-selling cookbooks on several lists. So it must have hit a chord.

A: We’ve had a tremendous re-sponse to Mexico—One Plate at a Time. The timing is great, as there’s a real boom in Latino culture in general. It also builds on what I and other people have been doing with previous cookbooks – the demystification process that encourages people to try something unfamiliar. Without a doubt, American palates are more adventurous.

Q: You’re about to start the second season of your public television show. How has television changed things?

A: The TV series Mexico—One Plate at a Time has allowed us to reach far more people than you can with a restaurant or cookbook. And again the response has been really wonderful. We hear from Americans who are tasting their first success with great Mexican dishes like chicken adobado or pozole. And surprisingly we’ve also heard from a lot of Mexicans now living in the States, saying that the show brought back memories of their mother’s or grandmothers cooking, and help them reconnect with their own roots. That’s been especially rewarding.

Q: You wanted to break the mold of the typical cooking show. How did you go about that?

A: We made Mexico a major character in the shows. Instead of just talking about Mexico, the magic of television lets us snap our fingers and go there, weaving places, people, dishes from Mexico seamlessly throughout the show. We can do our shopping in the great central market of Mexico City, pick up a few secrets from an ancient Aztec ruin or hit the hot new salsa club in Oaxaca. There are all these great connections between a culture and its food. So we explore them—and at a pretty fast pace.

Of course we’re still in the kitchen a lot. When it comes to the kitchen, I like to keep things real. And yes, that really is my home kitchen in the show. We do practically everything in real time and I always like to give the viewer a few options and alternatives. The point of the show is to make Mexican cuisine accessible and inviting.

Q: Can you get me a table at Frontera Grill for this Saturday?

A: We’ll have to get back to you on that. But it’s true that, after 15 years, on Saturday night when we open the doors, there’s a line long enough to fill the place. We must be doing something right.

https://web.archive.org/web/20030219055147/http://www.fronterafoods.com:80/television/qa.html

Chicago Tribune: Remarkable Woman, Deann Groen Bayless

http://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/ct-tribu-remarkable-bayless-20131103-story.html

Art Collection: Rolando Rojas

Rolando Rojas’ current works of art, which often combine earth with oil paints, reflect the current Oaxacan school of painting with its texture and tones. This young artist’s early training was in architecture and later in art restoration. These two applied fields of study allowed him to make a living in the colonial city of Oaxaca and to finance his painting career. During the early nineties, Rojas was given the tremendous honor of painting a mural in one of the side chapels of this city’s revered Basilica de la Soledad. This commission combined his love of painting with the education and training he had received.

Rolando Rojas’s paintings generally depict festive and happy times. His figures are not specific individuals, but rather the essence of people interacting—both man and woman at the same time. They are ageless and timeless characters at play. The creative way in which he works out his paintings is far more intuitive than the calculated and precise methods he learned as an architect. Rojas begins by applying a few brush strokes onto the canvas and then allowing the shapes and medium to emerge and define itself rather than imposing the forms and ideas from the onset. This method of painting, although not based in a formal and rigid discipline, is only possible because of his early career in architecture, in which drawing, composition and the understanding of space were critical tools to be mastered.

https://web.archive.org/web/20070216153957/http://www.rickbayless.com:80/restaurants/art/rojas.html

Art Collection: Cartonería

Cartonería refers to the type of popular art objects made especially for many Mexican festivals. Cartonería is very similar to papier-mâché, but utilizes cardboard and some paper (newsprint and brown butcher paper) pasted together and modeled with a hardening wheat-flour paste. The inner armature of a larger piece is made of a Mexican reed called carrizo. Once dried, the brown cardboard surface is primed with a layer of white paint or gesso, and then painted with colors.

Cartonería refers to the type of popular art objects made especially for many Mexican festivals. Cartonería is very similar to papier-mâché, but utilizes cardboard and some paper (newsprint and brown butcher paper) pasted together and modeled with a hardening wheat-flour paste. The inner armature of a larger piece is made of a Mexican reed called carrizo. Once dried, the brown cardboard surface is primed with a layer of white paint or gesso, and then painted with colors.

Decorative, lightweight and inexpensive cartonería objects and toys are produced in multiples and usually only last through an approaching holiday. Judas figures are biblical or political effigies created to be blown up with fireworks during Holy Week. Piñatas are created with cartoneria techniques for a multitude of children’s celebrations. These ephemeral popular works of art are intentionally burned or broken, and then replaced with new ones in the following year’s celebration.

Many artists in Mexico today have used this simple and traditional medium to create one-of-a-kind works of art. The most recognized and collected of these artists is the Mexico City-based Linares family. Now in their fourth generation of working cartonería, they have created a unique fine art form copied by many artists and artisans alike in the fantastic creatures known as Alebrijes (a word coined by Don Pedro Linares that has no roots in either the Spanish or Indigenous languages). Alebrijes belong as much to the fine arts category as to the popular arts. Sometime in the 1950s, Don Pedro Linares (1906-1992), a second-generation cartonería toy artisan, became extremely ill and had an intense feverish nightmare. When his fever finally broke, he began to create some of the fantastic creatures he had seen in this “other world” experience. This was the origin of the now world renowned Linares Alebrije legacy.

Many artists in Mexico today have used this simple and traditional medium to create one-of-a-kind works of art. The most recognized and collected of these artists is the Mexico City-based Linares family. Now in their fourth generation of working cartonería, they have created a unique fine art form copied by many artists and artisans alike in the fantastic creatures known as Alebrijes (a word coined by Don Pedro Linares that has no roots in either the Spanish or Indigenous languages). Alebrijes belong as much to the fine arts category as to the popular arts. Sometime in the 1950s, Don Pedro Linares (1906-1992), a second-generation cartonería toy artisan, became extremely ill and had an intense feverish nightmare. When his fever finally broke, he began to create some of the fantastic creatures he had seen in this “other world” experience. This was the origin of the now world renowned Linares Alebrije legacy.

Three works of art at Frontera Grill were made by the youngest of Don Pedro’s three sons, Miguel Linares (b.1946), who continues work in Mexico City with his family. His son Ricardo Linares (b.1966) also has acartonería “skull-scene” on display at Frontera Grill. This fourth generation artist creates pieces with a slightly darker/ominous side than those of his father and grandfather. There is clearly more influence from Hollywood movies, heavy metal rock en español and modern-day life in a more aggressive Mexico City.

Three works of art at Frontera Grill were made by the youngest of Don Pedro’s three sons, Miguel Linares (b.1946), who continues work in Mexico City with his family. His son Ricardo Linares (b.1966) also has acartonería “skull-scene” on display at Frontera Grill. This fourth generation artist creates pieces with a slightly darker/ominous side than those of his father and grandfather. There is clearly more influence from Hollywood movies, heavy metal rock en español and modern-day life in a more aggressive Mexico City.

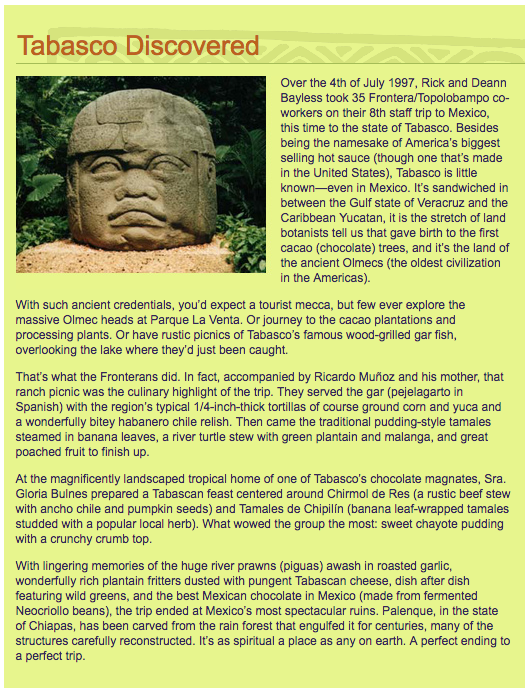

Frontera Staff Trip 1997: Tabasco Discovered

https://web.archive.org/web/20070515134259/http://www.rickbayless.com:80/about/notebook/tabasco.html

Los Surfos: check out the large photo archive from the first 2 years of Chef Rick Bayless’ restaurants at 900 W. Randolph St.

Pingback: Los Surfos | 3rdarm.biz